The author relates his rescue from German occupied Hungary in 1944 together with 1684 Jews aboard the Kasztner train that would lead him from Budapest—by way of a five months stay in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp—to Switzerland. It is about the loss of dignity and strategies for its recovery. What was it like to be an adolescent in these circumstances? Could an adult better support such a loss than an adolescent whose life and father image have been damaged? The subtext of this memoir is an open question: can we understand the suicides of many former camp inmates as delayed reactions to the loss of dignity they have suffered?

Une version plus longue de ce texte, parue en 2015 dans la revue Mozgo Vilag, a rencontré un écho auquel je ne m’attendais pas en Hongrie. Sans doute parce qu’il s’agit d’un des derniers témoignages sur l’épisode du « train Kasztner » qui a permis le sauvetage de plus de 1 600 Juifs hongrois en 1944. Mais vraisemblablement aussi parce que le médecin psychopathologiste de Budapest, Leopold Szondi, qui apparaît à la fin de ce récit, était connu du public cultivé hongrois. Après quarante ans de régime communiste qui n’avait encouragé ni les recherches sur la Shoah ni sur la « psychologie des profondeurs », le besoin de se réapproprier ces pages d’histoire est grand dans une société qui ne s’est jamais vraiment penchée sur son passé.

la version française du texte de Laurent Stern sera publiée dans le n° 3 de Mémoires en jeu (avril 2017)

The Gift of Shoelaces: Loss and Recovery of Human Dignity

IN MEMORY OF EDITH KURZWEIL (1924-2016)

What was it like to be in a concentration camp during the Holocaust? In answering this question, I must rely on my readers’ ability to imagine what it is like to temporarily lose their human dignity, whether slowly, gradually, or all at once. This is hard to do, for we are not immediately conscious of our loss, any more than we are aware of the moment we fall asleep. Moreover, our sense of shame prevents us from appearing without dignity on the stage of our mental life. Yet, only by reflecting on the loss of human dignity and the strategies for its recovery can we hope to provide an adequate answer.

I was born in Budapest in 1930. So I was only 14 when, in 1944, I spent five months as an inmate of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. I got there due to events of both political and family histories. The incorporation of Austria into the third Reich (Anschluss, March 1938) and Hungary’s first two anti-Jewish laws (May 1938 and May 1939) signaled the perilous situation of Hungarian Jews. After the Anschluss, every member on my father’s side of my family held a passport and, by the summer of 1939, even a British visa – all impossible to use once the war broke out. In the fall of 1939, they began to discuss various unpromising options, such as sending at least the family’s underage children to safety in one of the neutral countries, and they would mention Turkey, Spain or Portugal.

I did not know the details of these plans. Still, I sensed an immediate threat when refugees from Bratislava and distant relatives from afar were guests at our dinner table. From them, I heard about deportations and other acts of cruelty. I did not learn until much later that they were speaking of the deportation of people of unclear citizenship to Kamenets-Podolsk (1941) and about the mass murders of Novi Sad (1942). My parents, as well as all my ancestors, were born in the territory of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, but as a result of the 1920 peace treaty signed at Versailles, their place of birth fell outside of Hungary, and they were no longer Hungarian citizens when I was born. In the 1930s they had been granted citizenship, but as recent Hungarian citizens, my father’s family felt itself at risk.

By the beginning of 1944, my parents were seriously considering the possibility of a Kindertransport to a neutral country, and they outfitted me as if I were about to be sent off to a boarding school. After the German occupation of Hungary (on March 19, 1944) they thought about every possible means of escape for the twenty-nine members of our family.

The deportation of Jews from the Hungarian countryside began on May 15. In Budapest anyone who cared to find out could know within weeks that in Auschwitz an extermination camp was established. There were numerous Polish citizens living and working in Budapest – including thousands of Jews with false documents. This was known to the authority that controlled foreigners. People from Poland knew about the persecution of Jews and mass murders, and they spread this news in Budapest. While my parents had kept the earlier deportations to Kamenets-Podolsk and the mass murder in Novi Sad a secret, they let me know about the extermination of the Hungarian Jews of the countryside. Encouraged by them, I told our dentist and his assistant in detail about Auschwitz no later than in early June.

We knew of two possibilities to emigrate. Predatory smugglers offered to take small groups across the border to Romania with the help of SS members. They actually did this a few times. Most of the time, however, they just robbed these completely helpless people. Eight members of my father’s family, two couples with four small children and my maternal grandmother were also entrapped by one of these smugglers. He was to take them to Romania in exchange for a fortune, but delivered them to the nearest deportation center and thus ultimately to Auschwitz. They dropped a postcard from the train, addressed to Fülöp Freudiger, a mutual acquaintance and member of the Budapest Jewish Council. The SOS message written on the back of a photo of the two children was delivered to the address by an unknown good Samaritan. My two uncles sent two postcards to the same address, ostensibly from a resort called Waldsee, but actually – as you could see under a magnifier – from Auschwitz. By the time these messages arrived in Budapest around June 25, the four children and my maternal grandmother had been murdered.

My older uncle and his wife survived the war, found their child who had been hidden in Hungary. After the war they had four more children. My younger uncle died in January 1945. His wife remarried and had two children. The survival of the two young women would have been impossible, had they not taken my maternal grandmother’s advice who, upon arrival in Auschwitz, presented herself as the caregiver and sole relative of the four children. Her advice indicates that the adults travelling on the trains knew full well what was awaiting them at their destination. They knew that old people, children and those unable to work had no chance of survival. It is impossible that the leaders of the Hungarian state, army, and churches of all denominations did not know what as a fourteen-year-old I already knew. Yet, forty years later I found it unbelievable that well informed, talented Hungarian thinkers and writers were seriously debating three questions: who knew about Auschwitz, when and what? I have answered the first two questions. The answer to the third is, everything.

On March 19, 1944 Adolf Eichmann and his colleagues arrived in Budapest. They came to deport the Jews and remove them to concentration and extermination camps. Soon, they contacted Fülöp Freudiger, a member of the Jewish Council; they also established contact with the aid organization Vaad Hatzalah, led by Rezső Kasztner—a lawyer and active participant in the Zionist movement—and Joel Brand, among others. The aid organization tried to arrange the emigration of larger groups. We only knew that these negotiations began a few days after the occupation of Hungary. While we knew nothing about the relative power of the negotiators, we completely trusted those representing our interests, and distrusted the SS officers representing the other side – they were part of the Axis powers and might send us to Auschwitz at any moment. The SS officers who worked with Eichmann — Kurt Becher, Hermann Krumey and Dieter Wisliceny — played a particularly important role. As it turned out, Eichmann was the only one in favor of deportations to the end, even after July 7, when the Governor of Hungary wanted to stop them. However, his three colleagues tried to come to an arrangement with Rezső Kasztner’s organization. Eichmann, the SS leadership, and Himmler – according to his diaries – knew about these negotiations. However, the three officers also lined their own pockets. On May 14, they made their first proposal to Joel Brand: they offered to send Jews to neutral countries in exchange for trucks – they would release one hundred thousand Jews for every thousand trucks; for ten thousand trucks, they would release one million Jews. They also told Brand that deportations from Hungary would start the next day; and that twelve thousand Jews will be sent to Auschwitz every day.

Much earlier, Dieter Wisliceny had urged a similar deal in Slovakia by negotiating with the Working Group—the so-called Europa Plan. Although the Slovakian Group would not get trucks or other goods, they could collect enough money to bribe the Slovakian and German authorities. That was how they tried to halt the deportations. The Slovakian leaders, Gizi Fleischmann (1897–1944) and Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandel (1903–1956) remained convinced that they had succeeded—between 1942 and 1944. (Not all historians agree. Yehuda Bauer, author of Jews for Sale? twice changed his view. Most probably, they managed to bribe the Slovakian authorities at least temporarily.) In Weissmandel’s assessment, it was worth trying Wisliceny’s plan in Hungary. He wrote a letter to Freudiger about this in Hebrew, which was delivered by Wisliceny in the last week of March 1944.

All we knew at the time was that negotiations were in progress. Both sides were convinced the war would be ending soon. Although the Germans did speak of a wonder weapon capable of deciding the war in their favor, did they actually believe their own propaganda? If they did, the chief goal of continuing the negotiations could be nothing but the enrichment of the SS and the SS officers participating in the negotiations. If they did not, they may have been trying to ensure not only their personal enrichment, but also their exoneration after the war. They may have expected the help of the Jewish parties to the negotiations in this respect. Eichmann and his associates were war criminals, many of whom also participated in mass murders. The fact that Krumey and Becher escaped punishment after the war and the latter became exceptionally rich – allegedly, the richest person in West Germany in 1960 – suggests that their calculations were correct.

The Jewish negotiators had to take into account that neither the Allies nor the neutral countries wanted to admit large numbers of Jewish refugees. That already was clear at the Evian Conference (July 6-14, 1938). Under these circumstances Joel Brand was sent to Istanbul on a diplomatic plane two days after the first trains left for Auschwitz on May 15. Then and a few days later in Aleppo, he passed the offer of Eichmann’s colleagues to the representatives of the Jewish organizations. The only leading politician he could contact—before his arrest by the British authorities on suspicion of being a German spy—was Moshe Sharett, who became Israel’s Prime Minister ten years later. After his release on October 5, nearly five months later, it would have been pointless for him to return to Hungary and tell about the failure of his mission. At the time no one in Budapest knew about it. Rezső Kasztner continued to negotiate with the Germans.

While Kasztner’s goal was that at least one large group would leave Axis territory, he hoped that several others would follow. Allied victory became ever more certain. A day after the landing in Normandy, we read about it in the papers. A day later, we learned that a bridgehead had been secured. These accounts were tightlipped, but sufficient for an appraisal of the military situation. While the war touched our lives ever more closely, haggling continued. In June, Budapest was hit by air strikes, and the occupying authorities demanded the eviction of many Jewish families. Those forced to empty their apartments could only take along a minimum of clothes with them.

Zionist, reform, orthodox and other Jewish organizations were trying to get on Kasztner’s list—in proportion to their ratio among Hungarian Jews. There were separate places for rabbis, scholars and those deemed exceptionally talented. The wealthy paid for their own places and thereby funded those who could not afford it. On Friday, June 30, 1300 persons on the final list were issued invitations to gather on Kolumbusz Street, to get on a train headed to a neutral country. My family and I were on the list.

There were twenty of us from my father’s family, and one of my aunts brought her nephew, who was about seven. Since my father was the secretary of the Budapest Orthodox Jewish community, the four members of his family were included in the list allocated to the community. My three uncles paid for the other passengers in our family. It should be noted here that the German negotiators received about one thousand dollars per person—an amount easily obtainable by a middle class family within Hungary’s borders, in spite of the laws that expropriated Jews of their foreign currency, jewelry and stocks.

There were Jewish industrialists managing their factories from behind the scenes with the assistance of a figurehead-boss. Their forced collaboration in the war effort had a salutary side effect. They could keep in their factories large amounts of cash with the full knowledge of the fiscal authorities for paying the salaries of their workers. They also supported from these funds countless refugees in Budapest, and paid bribes extorted from them for their own survival. The Budapest black market rate was 35 Pengő to a dollar—a rate even the SS accepted. Yet, the German negotiators insisted on receiving hard currency from abroad. We and the Jewish negotiators were unaware of the importance of this stipulation and the reasons for it; it is quite likely that the German side was just as clueless in this respect until the very end of the negotiations in November 1944.

When we got to the gathering point, we found a huge crowd. The chaos was enormous. The Hungarian soldier who guarded the gate fired a shot into this crowd, but fortunately only caused a superficial injury to an elderly person near me. A doctor in our group provided first aid. No one checked our documents. Hundreds arrived without invitations, and some left despite having invitations. Later we learnt that our group consisted of 1684 persons. We marched to the nearby Rákosrendező train station and spent a long hot afternoon waiting on an empty platform. Later, when the heat was less oppressive, the younger people began to sing merry songs. An older railway man came up to us and asked a pair about to start dancing, “What are you so happy for? Don’t you know where you’re going?” He added, “One way or another…” while moving his left thumb across his throat. The oldest boy among us asked him, “Why, where are we going?” The railway man replied: “Auschwitz.”

My father overheard the conversation, and, as soon as we were alone, he assured me that we were better informed about our destination than the railway man. Yet, I often remembered this scene. After sunset, when a freight train rather than a passenger train arrived for us, we suspected that we were caught in a trap just like my maternal grandmother and the families of my two uncles. Night had fallen by the time our train left. Due to natural darkness and the blackout regulations dictated by the frequent air raids, we had no idea of the direction our train was taking, and only realized on the following day that we were still in Budapest – during the night we had traveled from one railway station to another. Apparently the threat of an air strike had made that trip necessary.

When our train finally left a few hours later, we went as far as Mosonmagyaróvár, about ten miles from the Austrian border. We spent the following three days in an open field, in relative comfort. Our seemingly carefree behavior in this idyllic early summer landscape made us look like tourists enjoying an outing rather than refugees facing an uncertain future. Even the weather was favorable: not too hot during the day, not too cold at night. Since I had spent summers near Lake Balaton, I was glad that we were not bothered by mosquitoes or flies. Our organizers bought food and fresh fruit from local farmers, and as far as I can recall we ate well. We knew, of course, that our train’s unplanned stop close to Hungary’s border was not auspicious, but assumed that an explanation would be forthcoming.

Late in the afternoon on the third day, we noticed ten or twelve SS soldiers with machine guns surrounding our open field. We did not know why. I expected to be in the crossfire of machine guns. My three years older sister and I were standing near the middle of the field, when somebody said we were heading for Auschwitz. Many persons sidled to the freight train, and a few stayed put as if their feet had been glued to the ground. This was the first time I saw how one could—at least temporarily—lose one’s dignity. A few feet from us, a bearded elderly man wearing traditional Hasidic clothes was rolling on the ground, shouting in Yiddish—rattevet mech! “Save me!” This did not bewilder us, for we expected to be saved. Nor did his hysterical reactions, for those seemed justified in the face of certain death. What we found unbearable was the next sentence, “You don’t know who I am.”

We knew. Joel Teitelbaum – Reb Jajlis to his disciples – was the rabbi of Szatmar, Chief of the Hungarian Board of Orthodox Rabbis, who later became an important leader of one branch of Hasidism in New York. We were involuntary witnesses to an outburst of panic. He temporarily lost his dignity, but it would be reprehensible to blame him—a victim. One of his disciples who often accompanied him hushed him, saying there were women and children around. Urged by our group leaders, we went back to our train and when all were aboard, we were surprised that the wagon doors were closed, but not locked from the outside. A few minutes later, we heard that our train was not going to Auschwitz, but to Auspitz in Austria. As our train was heading westward, we were certain that we were not being taken to Auschwitz.

On the following morning, we arrived at a station near Vienna. Pretty and kind young Austrian Red Cross nurses in clean, freshly ironed, bright red and white uniforms waited for us on the platform, and offered us excellent coffee and fresh Kaiser Rolls. At the sight of the nurses, it crossed my mind that a hot shower and a change of clothes wouldn’t hurt. I never forgot this fleeting thought because my wish soon partly came true. For now, however, the kind reception made us forget the previous day’s troubles.

Our train’s next stop was Linz. There we were told that we would be taken to a nearby bath, where women and men would bathe separately. We knew, of course, that in Auschwitz gas flowed from showerheads, but as yet were not worried about that. While the men stood in front of the building, the women were let into the bath. Soon we heard awful yelling and screaming. I could not stay nearby. So I walked down the platform and crossed the tracks towards a wood. As soon as I reached it, I sat down and thought for a few minutes. I could have escaped, but realized that I had no chance of survival without the group.

After I found my way back to where the men were still waiting, no one even asked where I had been. The screaming eventually subsided, and we learned that many women and older girls had had their hair cut, allegedly because of lice. The brutal SS bath tyrant ordered his underlings to engage in arbitrary cruelty. The only one I knew among those who had their hair cut was my sister’s friend and classmate—whose long braided hair I used to admire when she visited us in our home. She experienced what happened to her as humiliating, and could bear it only for a few days.

When it was finally the men’s turn, we were herded into a large hall, where we waited naked and tried to carry on a conversation while only looking at each other from the shoulder up. (Even years later, the younger men would recall that this was the first time they saw their fathers without clothes on.) After a long wait, we were finally disinfected and after a shower sent back to our train.

This train slowly rattled on towards Celle, and we eventually arrived at the train station near Bergen-Belsen. I have no specific memories of that part of the trip, except for the open wagon doors. The slowness of the train and its frequent halts were not reassuring. A day before we reached our destination, an old man suddenly rose to his feet and ran towards the door – as if wanting to jump out of the train. Those standing near the door restrained him.

On July 9, 1944, after a few kilometers’ walk from the train station, I arrived at the gate of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as a healthy, well-nourished teenager. We were assigned bunks, or won them in a fight. Now we lined up to be entered into the list of inmates. Our documents were still not checked. Upon returning to our barracks, everything seemed muddled. Just ten days earlier, I had been sleeping in my own bed, and what happened since then was beyond my powers of description. Feelings of fear and hope kept alternating. I was extremely shaken by the suicide of my sister’s friend; news of it spread fast. “Why?”– I asked. My silly question was met with the appropriate answer: “because they cut her hair.” I covered my mouth with both hands to stop myself from saying – “for that? But it’ll grow back!” Her body—the first corpse I ever saw—was removed on a wheelbarrow the following day. We took a few steps along its side. The dentist walking near me regretted that he had not had the chance to examine the deceased’s teeth, which would have helped to identify the body. Did he think that this body might end up in a peaceful village cemetery? I found his remark as inappropriate as my own stifled riposte.

Within a few days after arrival our health began to deteriorate. Dysentery, urinary tract infections and malnourishment did their job. We learned about the unsuccessful assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20 from a torn copy of the Völkischer Beobachter we found in the latrine. Even though we were starving, we rejected any food we deemed unsuitable for human consumption. Few of us knew that the edible snails (escargot), when properly prepared, even were a delicacy. Those of us in the know ate the snail soup and for once felt satiated, because they could eat the portions of all those who refused it. A few weeks of starvation took its toll: already by the beginning of September, I saw one of the wealthy members of our group rummage in the trash for discarded food scraps. Yet, our privileged camp did not have a single Muselmann—the name for the living dead—linger on. None of us had lost lost all hope for survival and we all kept fighting our fate. We never gave up hope.

At this point, I started to reflect seriously about my experiences since leaving home. I understood that I ought not condemn the persons who had behaved brutally at Kolumbusz Street; those who out of fear of death reacted hysterically near Mosonmagyaróvár; the one who due to a sense of confusion wanted to jump out of the train; or the one who chose voluntary death. We were all victims of the Hungarian and German state powers and their mobs. Our human dignity had been attacked. The theatre director of our youthful mental life makes sure that bodily pain is followed by forgetting. Only the damage to human dignity is unforgettable.

In the camp we moved between hope and fear. We knew there were negotiations about our fate already on August 16. Hermann Krumey appeared and announced that around 300 people would be temporarily admitted by Switzerland as refugees, and he would be accompanying them to the border. We did not know who compiled the list, but none of Rezső Kasztner’s and Joel Brand’s relatives were on it. Of course, many people wanted to be added to that list and Krumey was willing to give them a hearing. While standing within earshot, I heard Krumey’s sharp reply—Kommt nicht in Frage (Out of the question)—when one of my uncles asked for the 21 members of our family to be included. This temporarily deferred our chance for release. 318 people did leave our camp on August 18.

All along we used to complain about hunger, hardship and illness, but by late August, we also began to dread the one to two hour long Zählappell (roll call) held every morning in the cold and rainy weather of Northern Germany. Once during the roll call an SS soldier, who this time happened to be alone and without a dog, carefully looked around while putting an apple in the pocket of my aunt’s nephew. Even the little boy did not dare stir until after roll call—when he shared a bit of apple skin with the other children.

Bedbugs, lice, fleas and other insects caused damage. We often woke to the sound of mice scurrying on our bunks, and our straw mattresses stank with their excretions. The religious members of our group prepared for the fall holidays. We managed to get a shofar for the Jewish New Year from the neighboring Dutch camp. The required one hundred blows sounded in the morning of September 18 in our barracks, and this was repeated the next day. The older among the faithful had a hard time standing as required by the liturgy. The fasting of Yom Kippur fell on September 27.

* * *

A short digression. When I was a child, my tutors tried in vain to teach me disgust for foods that counted as prohibited from their viewpoint. They only could persuade me that whatever disgusted me was unsuitable for human consumption, and if nonetheless I consumed it, my human dignity would be damaged. They wanted to keep non-kosher foods away from me. My parents disapproved of this pedagogy, assuming that the Biblical commandment was the sole source of the prohibition. The quarrel between my parents and tutors had a surprising result: of all the foods I knew, the only one I found “disgusting” were pumpkins.

* * *

On September 27, 1944, our camp leadership managed to persuade the authorities to allow the distribution of food only after sunset in the evening following the Yom Kippur fast. When our dinner finally arrived, I immediately noticed that we were receiving pumpkin soup!

Now I had to choose between fasting for an additional twelve hours or eating the pumpkin soup. I fasted on Yom Kippur even though I no longer had any religious convictions. I would have preferred to eat, but that would have provoked the adults’ indignation – perhaps even their brutality. If I had overcome my “disgust” after the fast and eaten the pumpkin soup, I would have appeared to myself as a person rummaging in the trash, thus losing my human dignity. Therefore, I continued to fast until the following morning.

It is written: “Man does not live by bread alone” (Deut. 8, 3). To refuse bread might have been beneficial for my mental life later on—which I now doubt. Yet then my decision seemed satisfactory, so that for years I did not ask the superficial and obvious question: what does eating pumpkin soup have to do with dignity? The question could be turned around by wondering, what happens if one overcomes one’s notions about disgust? What does that have to do with the temporary or long-term weakening of one’s human dignity? In my twenties, when I asked myself this question, I found all the connections between pumpkin soup and human dignity irrational.

Other people are less fortunate. Incited by ignorant caregivers, they think of Blacks, Jews, Roma, Arabs, Serbs, Croats, gays, women or men with disgust and hate and may convince themselves that their own dignity would suffer unless they cast the objects of their disgust and hate out of society. However, what does their disgust and hate have to do with dignity? Do they believe that their own nobility can only be secured by the exclusion of others? After all, disgust or hate for fellow human beings does not secure one’s own human dignity. It simply leads to the humiliation of another—his temporary or permanent injury.

For me, the additional twelve hours of fasting were to save my human dignity. Adults had to devise other strategies. In the world of the starving, their strategy often revolved around food. Mothers occasionally managed to exchange a piece of clothing for an onion, and they also washed their family’s undergarments despite the poor water facilities. The fathers’ strategy was more likely to cause deep, long lasting wounds. Even non-addicted smokers from time to time would exchange a slice of bread for a cigarette—to regain temporarily their human dignity. Sometimes they competed within earshot of their children, about the sacrifices they had made to feed their children, and any child whose father had, in fact, not done so had to witness that father’s attempt to regain his dignity by lying. In an ordinary situation, this would have counted as a white lie, but in the world of constant hunger, such a lie destroyed trust.

Our schedule barely changed during October and November. Twice we were woken late at night and told we were going to take a shower. The nighttime adventure seemed too dangerous the first time, and I stayed on my bunk, claiming to be ill. The second time, I did go to the showers, accompanied by SS soldiers and their dogs; we were allowed a short time to wash ourselves before being rushed back to our barracks because of an air strike on the nearby town. During our walk, we perceived the light and noise of that air strike. It did occur to me fleetingly that those air strikes were a new danger to our group, but the unavoidability of death from above resembled the natural end of an individual life more than the mass death threatening us over the past few months.

One night the bass singer Dezső Ernster sang excerpts from Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. The politics of rejecting tyranny raised the hopes of the audience. When ten years later I heard him sing other roles in the New York Metropolitan Opera, I always gratefully remembered this evening.

News usually traveled fast in the camp, but one of the most crucial pieces of news failed to reach me: our group leaders were informed on November 18 that we would be able to leave the camp within two weeks. We were tipped off about this, when we were given Starkosan, a vitamin-fortified food resembling powdered chocolate, which was sent to us by the Swiss Red Cross. We received this about ten days before our departure and consumed it quickly. Even during these last days, our mood swung between hope and dejection.

We did not know it at that time, but on November 5, a meeting in Zurich at the Savoy Baur-en-Ville Hotel between an American diplomat, Roswell McClelland—who represented the US War Refugee Board in Switzerland—and Kurt Becher—who represented Himmler—was decisive for our group’s fate. For Himmler more than extortion and blackmail was at issue when he insisted that the hard currency for our release had to come from abroad. He intended to use bargaining about our group in order to be recognized as a valid partner in future diplomatic negotiations with the Allies and neutral countries. While his representative gained contact with a high-ranking American diplomat, this negotiation was utterly fruitless from the Germans’ perspective. Becher was told what he already knew, that Germany had lost the war and had to meet the Allies’ demands for unconditional surrender.

It was finally announced on December 4 that we had to walk to the nearby train station in the early afternoon. It was closer to evening when we arrived there. We were sitting on our bags on the bare railway platform, waiting in the cold drizzle until our train arrived 5-6 hours later. The wait was not promising, and it often crossed our minds that our train might take us to another concentration camp instead of Switzerland. When a passenger train rolled in rather than a freight train, our fear began to subside.

The train clunked along to the Swiss border for two days. Our progress was very slow due to air strikes. My oldest cousin got off at a station. While he was smoking a cigarette, the SS soldier guarding the train asked him, what a German child did to deserve to be killed by an air strike? My cousin answered that he was right, but the Jewish child did not deserve to be murdered either. The guard began to beat my cousin with his rifle butt in frenzy.

[I told this story to Rabbi Weissmandel in the New York Public Library ten years later. He responded by telling me about the time he asked the bishop of Nyitra to save innocent Jewish children from deportation. The prelate answered that there was no such thing as an innocent Jewish child. What was the difference between the god-fearing prelate, raised on traditional theology, and the advocate of race theory? Who felt more moral outrage and human affection?]

The negotiations about our fate continued until, finally, on December 7, we changed to a Swiss train for entering Switzerland. We crossed the border at St. Margrethen at around 1 A.M. When the border guard asked my name and advised me that he had to list me as “Laurent Stern” rather than “Stern Lóránt,” according to local customs and rules of spelling, I was too tired to argue. I thanked him for his care and spelling lesson. I soon celebrated this as my rebirth and never again used my birth name outside Hungary.

Early next morning we were walking to a large building resembling a school. Rezső Kasztner—who was temporarily in Switzerland after the end of the negotiations—noticed me from the sidewalk and asked me to stay put and to wait for him to return. He brought me shoelaces to replace the twine that I used in the camp. What his gift taught me was the importance of shedding the appearance of a besprizorni—homeless teenager—as a strategy for regaining human dignity.

On that day, in St. Gallen a young Swiss doctor made me understand the effects of the previous five months in the camp. So far, I had only seen the signs of our suffering with my own eyes, but as we lined up naked for disinfection, and that doctor asked each person’s name, age and profession, I first perceived what we looked like through another’s eyes.

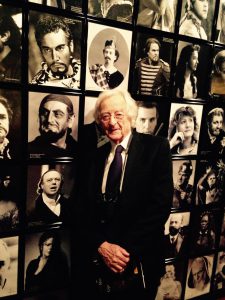

In the camp, I had seen the man who now stood ahead of me in that line, usually with his son, who was about my age. When he replied (Leopold Szondi, 51 years old, psychiatrist), the Swiss doctor remarked that he had recently studied a brilliant book entitled Schicksalanalyse (Fate-Analysis) – was it perhaps written by a relative? “Not a relative,” the man responded, “I am the author of the book.” On hearing this, the Swiss doctor groaned, fainted, and collapsed.

I cannot know why the Swiss doctor lost consciousness for a few seconds. Yet, I recall how I experienced this scene: our miserable appearance revealed that our dignity had been—at least temporarily—damaged. Every day we wanted to survive for just one more day. Of course, the struggle entailed no guarantee of escape from the constant threat we faced. However, it made suicide impossible, for that would have meant the victory of those who terrorized us. The only “free” death in the camp occurred before the struggle for survival began.

After our release, I heard of other inmates’ suicides; the first happened three months after our arrival in Switzerland, the last occurred several decades later. Suicides are always multiply determined. We need not search for detailed answers to the question why each chose to end their own life. No doubt, they were depressed. Why? Physical injuries often allow for complete recovery; their scars rarely serve as reminders. Our health returns much faster in youth than in adulthood. Mental injuries, however, are more successfully overcome in adulthood than in youth. In these cases, years later we can still feel the physical pain inflicted by very old violence and experience it as an attack on our human dignity.

When the Swiss doctor looked at the naked people lined up in front of him, he saw the signs of hardship and of open wounds caused by insects. Behind these, he also saw the horror and the mental damage these had caused. Of course, he had no way of knowing that the man standing before him would die 42 years later in his bed, at the age of 93, and that his son Peter would become a world-famous scholar, and far surpass his father’s fame. Or that this son would choose voluntary death at 42, after he had achieved all that he had ever hoped for.

After leaving Budapest, we did not wear yellow stars, did not have to work and—except for the cruelties already mentioned—we had not suffered brutal treatment. On the road leading to Auschwitz, we were only temporarily deprived of our human dignity. Those who experienced more cruelty and had to bear it for longer than we, came closer to the suffering of victims murdered in Auschwitz. No doubt, the victims there or in any other extermination, concentration or labor camp run by the Axis powers elsewhere lost more than their dignity. However, their murderers prepared them for their ultimate fate by depriving them of their human dignity. For this reason, their fate would be inexplicable without our prior understanding of their loss of dignity. The Swiss doctor saw at a glance the role of mental injuries in our lives, even though he could have no idea about its long term effect.*

*Translated from Hungarian by Katalin Orbán and revised by the author.